Not all data breaches are created equal — do you know the difference?

It was one of those typical, cold February winter days in Indianapolis earlier this year. Kids woke up hoping for a snow day and old men groaned as they scraped ice off their windshields and shoveled the driveway. Those were the lucky ones, because around that same time, executives at Anthem were pulling another all-nighter, trying to wrap their heads around their latest data breach of 37.5 million records and figuring out what to do next. And, what do they do next? This was bad — very bad — and one wonders if one or more of the frenzied executives thought to him of herself, or even aloud, “At least we’re not Sony.”

Why is that? 37.5 million records sure is a lot. A large-scale data breach can be devastating to a company. Expenses associated with incident response, forensics, loss of productivity, credit reporting, and customer defection add up swiftly on top of intangible costs, such as reputation harm and loss of shareholder confidence. However, not every data breach is the same and much of this has to do with the type of data that is stolen.

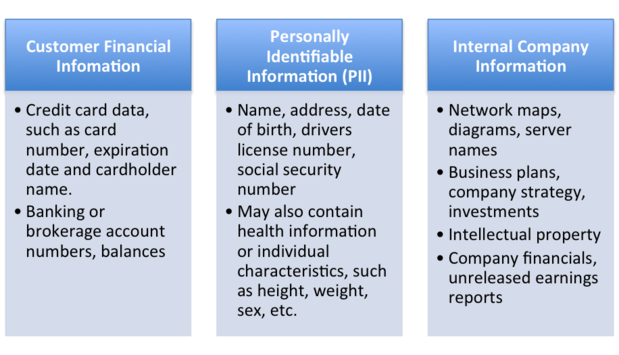

Let’s take a look at the three most common data types that cyber criminals often target. Remember that almost any conceivable type of data can be stolen, but if it doesn’t have value, it will often be discarded. Cyber criminals are modern day bank robbers. They go where the money is.

Common data classifications and examples

Customer financial data

This category is the most profuse and widespread in terms of the number of records breached, and mostly includes credit card numbers, expiration dates, cardholder names, and other similar data. Cyber criminals generally pillage this information from retailers in bulk by utilizing malware specifically written to copy the credit card number at the point-of-sale system when a customer swipes his or her card. This is the type of attack that was used against Target, Home Depot, Neiman-Marcus and many others, and incidents such as these have dominated the news for the last several years. Banks have also been attacked for information on customers.

When cyber criminals then attempt to sell this pilfered information on the black market, they are in a race against time — they need to close the deal as quickly as possible so the buyer is able to use it before the card is deactivated by the issuing bank. A common method of laundering funds is to use the stolen cards to purchase gift cards or pre-paid credit cards, which can then be redeemed for cash, sold, or spent on goods and services. Cardholder data is typically peddled in bulk and can go for as little as $1 per number.

Companies typically incur costs associated with response, outside firms’ forensic analysis, and credit reporting for customers, but so far, a large-scale customer defection or massive loss of confidence by shareholders has not been observed. However, Target did fire its CEO after the breach, so internal shake-ups are always a stark possibility.

Personally identifiable information

Personally Identifiable Information, also known as PII, is a more serious form of data breach, as those affected are impacted far beyond the scope of a replaceable credit card. PII is information that identifies an individual, such as name, address, date of birth, driver’s license number, or Social Security number, and is exactly what cyber criminals need to commit identity theft. Lines of credit can be opened, tax refunds redirected, Social Security claims filed — essentially, the possibilities of criminal activities are endless, much like the headache of the one whose information has been breached.

Unlike credit cards, which can be deactivated and the customer reimbursed, one’s identity cannot be changed or begun anew. When a fraudster gets a hold of PII, the unlucky soul whose identity was stolen will often struggle for years with the repercussions, from arguing with credit reporting agencies to convincing bill collectors that they did not open lines of credit accounts.

Because of the long-lasting value of PII, it sells for a much higher price on the black market — up to $15 per record. This is most often seen when companies storing a large volume of customer records experience a data breach, such as a healthcare insurer. This is much worse for susceptible consumers than a run-of-the-mill cardholder data breach, because of the threat of identity theft, which is more difficult to mitigate than credit card theft.

Company impact is also very high, but is still on par with a cardholder data breach in that a company experiences costs in response, credit monitoring, etc.; however, large-scale customer defection still has not been observed as a side effect. It’s important to note that government fines may be associated with this type of data breach, owing to the sensitive nature of the information.

Internal company information

This type of breach has often taken a backseat to the above-mentioned types, as it does not involve a customer’s personal details, but rather internal company information, such as emails, financial records, and intellectual property. The media focused on the Target and Home Depot hacks, for which the loss was considerable in terms of customer impact, but internal company leaks are perhaps the most damaging of all, as far as corporate impact.

The Sony Pictures Entertainment data breach eclipsed in magnitude anything that has occurred in the retail sector. SPE’s movie-going customers were not significantly impacted (unless you count having to wait a while longer to see ”The Interview” — reviews of the movie suggest the hackers did the public a favor); the damage was mostly internal. PII of employees was released, which could lead to identity theft, but the bulk of the damage occurred due to leaked emails and intellectual property. The emails themselves were embarrassing and clearly were never meant to see the light of day, but unreleased movies, scripts and budgets were also leaked and generously shared on the Internet.

Many firms emphasize data types that are regulated (e.g. cardholder data, health records, company financials) when measuring the impact of a data breach, but loss of intellectual property cannot be overlooked. Examine what could be considered “secret sauce” for different types of companies. An investment firm may have a stock portfolio for its clients that outperforms its competitors. A car company may have a unique design to improve fuel efficiency. A pharmaceutical company’s clinical trial results can break a company if disclosed prematurely.

Although it’s not thought of as a “firm” and not usually considered when discussing fissures in security, when the National Security Agency’s most secret files were leaked by flagrant whistleblower Edward Snowden, the U.S. government experienced a very significant data breach. Some would argue it is history’s worst of its kind, when considering the ongoing impact on the NSA’s secretive operations.

Now what?

Whenever I am asked to analyze a data breach or respond to a data breach, I am almost always asked, “How bad is it?” The short answer: it depends.

It depends on the type of data that was breached and how much of it. Many states do not require notification of a data breach of customer records unless it meets a certain threshold (usually 500). A company can suffer a massive system intrusion that affects the bottom line, but if the data is not regulated (e.g. HIPAA, GLBA) or doesn’t trigger a mandatory notification as required by law, the public probably won’t know about it.

Take a look at your firm’s data classification policy, incident response and risk assessments. A risk-based approach to the aforementioned is a given, but be sure you are including all data types and the wide range of threats and consequences.

Originally published at www.csoonline.com on March 17, 2015.